Women Among Us: Terry Galloway

Terry L. Galloway is a deaf writer (poetry, essays, memoir, and plays), director, dramaturg, and performance artist who has an international reputation for scandalous humor combined with incisive insight. Her latest memoir, Mean Little Deaf Queer, has been described as "Running with Scissors meets The Liar's Club" and has just been published by Beacon Press. At this moment Terry is in London doing readings, but will soon return to the U.S. to continue her book tour in many cities.

She's the founder of Actual Lives theater troupe (for disabled adults), cofounder of the Mickee Faust Alternative Performance Club in Tallahassee, Florida, one of the founders of Esther's Follies in Austin, Texas, and a celebrated alumnus of Shakespeare at Winedale. From cabaret to the Bard, she's sunk her enthusiastic teeth into every aspect of theatrical expression and wrestled it into new life. I once saw her perform Allan Ginsberg's "Howl" dressed as a dog, and she had us alternatively convulsing with laughter and weeping from the sudden revealed meaning in Ginsberg's lines.

She was born in 1950 to military parents stationed in Germany. Her mother was treated with experimental antibiotics during her pregnancy with Terry, resulting in Terry being born with profound hearing impairment, some visual deficit, and other fetal nervous system damage. Medical mishap was followed by cultural suppression, as Terry was kept from learning sign language because the thinking of the times was that ASL was not a "real language" and lip-reading offered children a chance to be "normal". We now know this choice can rob a baby of any ability to develop language at all.

This calamity is exactly what happened to my Uncle Joseph, who was removed from my grandparents when he was a toddler and sent to the Texas State School because he had begun acting out in rage at his inability to communicate with others. He and the other children there developed their own pidgin form of sign language, a desperate attempt to break their isolation. Joseph was taught a rudimentary trade (shoe repair), married another girl from the school, and never learned ASL or English. He was estranged from most of the family except my mother and father, who made any effort it took to stay in touch with him and converse across the vicious barrier imposed on him by stupid theorists and administrators.

Terry Galloway's middle name should be overcompensation, because she not only became brilliant in the written and oral use of English, she went into theater. But she is no Johnny Belinda, no nice-girl-making-good. She is full-throttle Falstaff with an education and dyke smarts. And to tell you the whole of how I know this, I'll have to tell you something about myself as well.

On July 25, 2000, I had my left knee replaced. I had a great job, savings and sick time set aside, lots of friends to help me, and a good sports medicine surgeon. I made what I believed was an informed decision. I expected to be out of the hospital and into the rehab unit in a couple of days, home five days after that, walking again more or less normally in six weeks.

But a perfect storm of complications nearly killed me, at first outright and then by degrees. I had a period of anoxia during the surgery that went unnoticed. When I came out of anesthesia, I was on a morphine drip that everyone assumed was responsible for my altered mental state. I was not sure where I was, what was happening around me, or sometimes who were people I know have known well. My kidneys failed, a rare side effect to the anticlotting drug I was on left me unable to eat or drink, and I began having a period again despite having reached menopause. Mostly, though, I could not tell anyone what was going on inside my head. My ability to connect my thoughts to language had been hammered. And nobody noticed.

Well, one nurse did. But the doctors argued it was the morphine, and everybody treated me like I was being overemotional when I tried to get past the roadblock in my neurons.

I hope you never know the kind of terror I felt. I hope nobody ever does.

My third night in the hospital, I was physically abused by the overworked nurse on duty. When the evidence was discovered on my body the following afternoon by another nurse, she called in a coworker and they flat out stated to each other what had occurred, but they didn't document it or tell anyone else, just dressed the wound and told me I wouldn't be left in the care of that nurse again. I began refusing to cooperate with anyone, which got me in more trouble. The physical therapist trying to get me walking up and down the monstrously unfamiliar hallway actually screamed at me that I was going to wind up in a wheelchair and die if I didn't follow her instructions. Finally they shipped me to rehab, several days late, and I decided to work my ass off, get out of there and to safety -- anywhere else felt like safety.

But home turned out to be just as strange and frightening, because of my continuing inability to communicate. I had an 18 inch wound in my leg closed with staples. I couldn't wipe myself, I couldn't hear the phone ring, I couldn't write my name, I couldn't read, and a lot of TV sounded like it wasn't in English. My insurance didn't cover in-home care except for a daily 20 minute visit by a nurse or a PT, so one of my friends came once a day to make me a meal, help me clean up, and do a few essentials. Otherwise I was alone. People were calling me but I couldn't hear the phone and thus was not answering.

Mostly I slept, because when I was asleep, I wasn't terrified.

Three days after I was discharged, I returned to my surgeon's office to have my staples removed. Here's a tip: If you are not an athlete, don't choose a sports medicine specialist as your surgeon. They will not have a realistic set of expectations for you. And they're not likely to be what you'd call empathetic. A friend drove me to the office visit and stayed in the room with me while I got x-rayed, but looked away when the doc pulled out my staples. It didn't hurt, so I did watch. And thus I witnessed eight inches of my wound gradually reopening before my eyes, my skin parting in slow motion to a depth of two inches. The surgeon said "Uh-oh" and left the room. After half a minute, so did my friend. It was the doctor's assistant who explained I had a skin condition called dehiscence, which means wounds tend to not stay closed. Since I'd never had surgery before, we were just finding out about it.

I asked him how much longer I'd be in the hospital. He explained, kindly, that this was not considered enough of a problem to require hospitalization. Instead, I'd be bandaged and sent home. The wound would heal from the inside out -- they call it healing by secondary intention, and if you think I haven't tried to write a poem with that fabulously symbolic phrase in it, you don't know me very well. It would take months, and alter my physical therapy program. He added, as an afterthought, that the risk of infection was now very high, so I'd have to go to see the wound care nurse on my way home.

I was given a wheelchair and sent away. Getting in and out of the chair, the car, had now become even more problematic. My friend coped with it silently, tensely. When she wheeled me into the wound care room, I looked into the face of the physical therapist who had screamed at me in the hospital. We both froze.

I was able, by that time, to articulate in a vague what was going on with me, though mostly I still thought it was a reaction to the morphine. To the PT's credit, she apologized for her behavior and turned out to give me a lot of information I needed. Wound care is a euphemism for teaching you how to take care of your own wound when you're not in the hospital. I'll spare you the details. Let's just say I learned to do things I never would have believed I could. She packed up supplies, wished me luck, and I went back home, where my friend got me to my bed and rushed away because she was late for something.

Two days after that, I called another friend, Mack. She told me she'd been hired to videotape a theater project that was being taught by Terry Galloway. I knew about Terry Galloway, had attended every performance of her in Austin for years, some of them several times. I adored her work. Mack said the new project was called Actual Lives: A group of adults with various disabilities met every day for a week, learning theater and writing an individual performance piece about their life, with Terry's hands-on training. On the seventh day, they would perform their work for the public on stage. Mack said she could maybe get me into the group, but I'd have to go that night.

I told her I needed her to come and get me. She crabbed about it -- I lived at the opposite end of Austin from where she was and where the group was meeting. Finally she said I'd have to be ready and waiting on her. I agreed. I got my wheelchair out the front door and sat on my patio half an hour before she pulled up.

I couldn't tell if Terry recognized me from my many attendances at her plays -- I was too overwhelmed by being out of anything close to familiar, with all the clamor of that particular environment, and with feeling like maybe I wasn't a "real" disabled person. I hadn't eaten dinner, either. In the group were two blind women and two people with TBI. Terry was deaf but not a signer, so everything anyone said had to be repeated to her by someone whose lips she could read, plus all action had to be conveyed to the blind women by a visual interpreter. This simultaneous, exhausting translation was hard on the frail and those with cognitive hits on their attention span. There was more than one meltdown that night. But Terry kept pushing each of us, refusing to treat us with pity or keep a distance. She was in our faces -- literally, if she could read our lips -- assuming if we had shown up for this, we had something to say and she was going to make damned well sure we did it artistically, honestly, and with respect for our audience. We were not going to be "see how the poor crips kinda do a play", not on her watch.

I don't remember saying anything that first night with Actual Lives. I know for certain I didn't tell any of them what I was actually contending with. Mostly I remember watching, still in terror but there was a glimmer of hope on the horizon. At the end of the evening, Terry told us we had to go home and write a paragraph on something, I can't remember what the assignment was. I wheeled over to her and, eventually, got across to her that I couldn't write yet.

"Yes you can" she shouted at me. She didn't mean to shout, that much I understood. "You can write two fucking lines, I don't care what it is. I expect you to bring it tomorrow." Then she put her hand on my shoulder and said "No excuses."

I had to wait on Mack because she was gathering up her gear. There were several people in line to use the only wheelchair accessible bathroom in that place, and I stayed at the end of the line because I didn't want anyone to offer to help, to see the huge bandage on my leg. By the time I got into the stall, I'd pissed myself. Mack found a plastic bag in the back of her car and put it on her seat before I got in. Once at home, I told her I could deal with cleaning myself up and she left.

Eventually, I walkered to my computer and turned it on, the first time since I'd been home. Thank god I had the password written out on a piece of paper next to the monitor. It took me 15 minutes to get a fresh document opened, sitting there in front of me. It was another two hours before, drenched in sweat, I'd managed to type out three sentences. It was extremely bad writing, not quite making sense and certainly not what I wanted to say. But it was enough. I printed it out and went to bed.

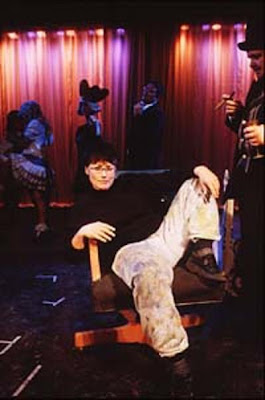

I honestly believe Actual Lives saved me. Mostly, it was Terry Galloway. She got to know me, each of us, so she could coax, lead, or hector us into doing the utmost of which we were capable. Over the next couple of years, I lost my job, my savings, most of my friends, and any financial security I'd had. The cat I lived for, my little brother, two of my oldest friends, and my beloved aunts died. I became absolutely a real crip, no doubt about it. But I met it all with courage and humor, instead of being mowed down, because Terry insisted (and modeled) that reality was what you made of it and art is the best transformative tool she knows. (Terry Galloway with Rude Mechanicals Theater Group in Austin, Texas; photo by Kenny Braun.)

(Terry Galloway with Rude Mechanicals Theater Group in Austin, Texas; photo by Kenny Braun.)

Early on, I tried to write about what happened to me in the hospital and rehab center. It was grim, desperate stuff. Terry was visibly affected by it, as she usually was by our stories. She weeps easily. She gives her heart away at a moment's notice. But one piece of writing she handed back to me, the account of a nightmarish night when I'd needed a tampon changed in the rehab unit and the staff who showed up had never used a tampon themselves. She told me to rewrite it as comedy. I can clearly remember that my immediate response, inside my head, was "Fuck you." Probably that showed on my face as well, because she leaned in to say, a little too loud, "It could be hysterical, if you give up wanting somebody to feel sorry for you."

I did rewrite it, over and over, until it became the second-best performance I ever created. It brought audiences to their knees, howling with laughter, and at the same time conveyed -- far more effectively than a straight approach would -- the intimate horror of that episode. Terry has recently staged it with her performance troupe in Tallahassee. If you want to read the final script, it's at the end of the post titled My Knees (Part Two -- Surgery and Rehab).

I trust Terry completely. She's never let me down. And from her shove back into writing, I went on to form my own writing group, to find other mentors, and to realize my voice as a writer.

In 2002, we both attended the first (and so far, only) Queer Disability Conference in San Francisco. We had rooms in the same dorm, on the same floor, and this incident happened repeatedly: I'd be in my dorm room when I'd hear a pounding on the door and Terry shouting "Maggie! Maggie! Are you in there?" I'd get painstakingly to my feet, lean on my quad cane and move slowly to the door. But once I got it open, I'd see Terry chugging impatiently down the hall toward her own room, her back to me. At which point I'd stupidly shout after her "Terry! Hey, Terry!" Then I'd smack my head, remembering she's DEAF, you dummy.

That itself would make a hilarious little vignette on stage, I think.

In the late 1990s, before Terry became a friend and mentor, I started a group studying the herstory of lesbian activism in Austin during the 1970s. Eventually I made a documentary about this era, interviewing many women about that period in their lives. One of the names which always came up was that of Terry Galloway, who despite being powerful and socially active appears to have made no enemies along the way. Extremely rare for dykes bent on revolution. I was highly entertained when two different women that I interviewed confided in me, off camera, that they were proud of having been "the woman who brought out Terry Galloway". I was even more entertained years later when I told Terry about it, and she snorted in reply "Neither one of them was my first lover!"

Terry's biography at Beacon Press reads:

Terry Galloway is a deaf, queer writer and performer, who tours her one-woman shows as a cheap way of seeing the world. She has performed her solo shows "Out All Night and Lost My Shoes" and "Lardo Weeping," in venues ranging from the American Place theater in New York to the Zap Club in Brighton, England. In Austin, Texas she gained a reputation for playing comic male roles as a student and Research Associate for the University of Texas' alternative Summer Theater Festival, Shakespeare at Winedale.

She's also known as one of the founding members of Austin's wildly popular 6th street cabaret Esther's Follies and as the founder of Actual Lives, a writing and performance workshop for adults with and without disabilities. In Tallahassee, Florida she is the Head Cheese of the Mickee Faust Academy for the REALLY Dramatic Arts and the co-founder of the Mickee Faust Club, a performance group responsible for the award-winning video parodies, "Annie Dearest, The Real Miracle Worker, " featuring lots and lots of wah-wah, and "The Scary Lewis Yell-a-thon," featuring a Jerry Lewis look-alike and a bevy of inspirational cripples. She writes as well as performs and you can find her articles, monologues, poems and performances texts in, among other publications, Sleepaway: Writings on Summer Camp, Cast Out: Queer Lives in Theater, Out of Character- Rants, Raves and Monologues from Today's Top Performance Artists, Plays from the Women's Project, Texas Monthly Magazine, Austin Chronicle, American Voice, The Dolphin Reader, and numerous anthologies about queerness, deafness, disability, theater, and Elvis.

She has been a Visiting Artist at the California Institute of the Arts, Florida State University, and the University of Texas at Austin. She's won a variety of awards including an NEA, a J. Frank Dobie Fellowship from the Texas Institute of Letters, grants from the Texas Commission of the Arts and the Florida Divisions of Cultural Affairs, five Corporation for Public Broadcasting Awards, three Prindi National Public Radio Commentary Awards, and a Best Swimmer Award from the Lions Camp for Crippled Children.

She splits her time between Austin Texas, and Tallahassee, Florida where she lives with her long-time love Donna Marie Nudd, a professor at Florida State University, and their cat Tweety.

Donna Marie Nudd and Terry Galloway, Dobie Paisano Ranch outside Austin, Texas, March 2008, photo ©Marsha Miller, University of Texas at Austin.

Donna Marie Nudd and Terry Galloway, Dobie Paisano Ranch outside Austin, Texas, March 2008, photo ©Marsha Miller, University of Texas at Austin.SELECTED WORK BY TERRY GALLOWAY:

Mean Little Deaf Queer, Beacon Press, 2009.

Out All Night and Lost My Shoes, play edited by Barbara Hamby, Tallahassee: Apalachee, l993.

In The House Of The Moles, unpublished play.

Lardo Weeding, unpublished play.

Deaf As A Post/Tough as Nails, performance at Queer Disability Conference, San Francisco, June 2002.

Out All Night And Lost My Shoes (solo amalgam performance, includes "Mr. Handchops"), performance at Queer Disability Conference, San Francisco, June 2002.

"Heart of a Dog" In The Women’s Project 2, edited by Julia Miles. New York: Performing Arts Journal, l984.

“Taken: The Philosophically Sexy Transformations Engendered in a Woman by Playing Male Roles in Shakespeare", Text and Performance Quarterly 17.1 (1997): 94-100.

What We Carried Away from Winedale, article in the Austin Chronicle, 23 July 2004

Go to the website for her book at Mean Little Deaf Queer , scroll down the page to the Contents and click on "The Performance of Drowning" to hear an MP3 of Terry reading her essay about winning a swimming award at the Lions Camp for Crippled Children. HIGHLY recommended.

One of Terry Galloway's screenplays and directorial efforts is the short Annie Dearest, by produced by Faust Films and Diane Wilkins. This is a video parody of the classic film The Miracle Worker, which originally starred Patty Duke as deaf/blind Helen Keller and Anne Bancroft as Anne Sullivan, Helen's mentor and tormentor. Disability World heralded Annie Dearest as one of the 25 most outstanding disability films in the last five years. This reveals Terry Galloway's trenchant humor at its best and limns her philosophy of refusing to be the inspirational sort of "good cripple". Co-creator Donna Nudd also stars in the video as "Annie Dearest".

ARTICLES ABOUT TERRY GALLOWAY:

Highly illuminating essay by Donna Marie Nudd, Terry's partner, titled Feminists As Invisible Dramaturgs: A Case Study of Terry Galloway's Lardo Weeping.

Two Generations, One Art by Robert Faires in the Austin Chronicle, 25 February 2000

QUOTES BY TERRY GALLOWAY:

“Deafness has left me acutely aware of both the duplicity that language is capable of and the many expressions the body cannot hide.”

"Reality which so often intimidates us is exposed as just another fiction. Ours for the rewriting." -- from "Deaf as a Post/Tough as Nails" performed for Queer Disability Conference, San Francisco, California 2002

QUOTES ABOUT TERRY GALLOWAY:

"This is not your mother's triumph-of-the-human-spirit memoir. Yes, Terry Galloway is resilient. But she's also caustic, depraved, utterly disinhibited, and somehow sweetly bubbly, a beguiling raconteuse who periodically leaps onto the dinner table and stabs you with her fork. Her story will fascinate, it will hurt, and you will like it." -- Alison Bechdel, author of FUN HOME

“This is a damn fine piece of work which is unbelievably powerful. This story is true and passionate and fearless and funny as hell when it is not heartbreaking. I expect this book to charm the hell out of great numbers of people, piss off a few, and give hope to many more...” -- Dorothy Allison

Donna Marie Nudd and Terry Galloway, Dobie Paisano Ranch outside Austin, Texas, March 2008, photo ©Marsha Miller, University of Texas at Austin.

Donna Marie Nudd and Terry Galloway, Dobie Paisano Ranch outside Austin, Texas, March 2008, photo ©Marsha Miller, University of Texas at Austin.

|